Discovery of the

Amarna Tablets

E.A. Wallis Budge

BEFORE I had been in Cairo

many hours I found that everybody was talking about the discoveries

which had been made in Upper Egypt, and the most extraordinary

stories were afloat.

Rumours of the "finds" had reached all the great cities

of Europe, and there were representatives of several Continental

Museums in Cairo, each doing his best, as was right, to secure

the lion's share. The British officials with whom I came in contact

thought, or said they thought, that whatever the objects might

be which had been discovered, they ought to go to the Bulak Museum,

and that any attempt made to obtain any part of them for the British

Museum must be promptly crushed. The Egyptian officials of the

Service of Antiquities behaved according to their well-known manner.

No official of the Bulak Museum knew where the "finds"

had been made, or what they consisted of, and M. Grebaut [Maspero's

successor as Director of the Service of Antiquities] and his assistants

went about the town with entreaties and threats to every native

who was supposed to possess any information about them.

Instead of recognizing the fact that, rightly or wrongly, the

finds" were at that moment in the hands of native dealers,

and trying to make arrangements to secure them by purchase, they

went about declaring that the Government intended to seize them

and to put in prison all those who were in any way mixed up in

the matter M. Grebaut was unwise enough to hint publicly that

the tortures which were sanctioned at Kana might be revived, but

the tortures and persecution of 1880 had taught the natives how

little Government officials were to be trusted, and one and all

refused to give him any information. Every move which he made

was met by a counter move by the natives, and they were always

successful.

Meanwhile very definite rumours about the "finds" in

Upper Egypt drifted down the river to Cairo, and some members

of the Government insisted that M. Grebaut should take active

steps to secure some of the treasures which had been found, and

they ordered him to make a journey to Upper Egypt, and find out

for himself what was taking place there. They placed one of Ismail

Pasha's old pleasure-steamers at his disposal, and ordered an

adequate force of police to accompany him. Before he left for

the South he called upon me at the Royal Hotel, and although he

threatened me with arrest and legal prosecution afterwards, if

I attempted to deal with the natives, I found him a very agreeable

and enlightened man, and we had a pleasant conversation. He told

me that his great ambition was to be regarded as a worthy successor

of Maspero, and that there was one mark of public recognition

which I could help him to obtain. The Trustees of the British

Museum, he reminded me, had presented a set of their magnificent

Egyptological publications to Maspero, which was a very distinguished

mark of honour, and a public acknowledgment of his scholarly eminence,

and he hoped that the Trustees would honour him in the same way.

I told him that I thought he might do a great deal towards getting

that honour by adopting a liberal policy in dealing with their

representative in Egypt, and that in any case I would duly report

the conversation to the Principal Librarian. That same evening

I learned that he had told off some of his police to watch the

hotel in which I was staying, and that he had ordered them, to

report to him my goings out and comings in, and the names of all

antiquity dealers who had speech with me.

I left Cairo that night for Asyut, and soon after leaving Bulak

ad-Dakrur station I was joined in the train by a Frenchman and

a Maltese, who told me that they were "interested" in

anticas, and that there were police in the train who had been

ordered to watch both them and me. At Der Mawas, the station for

Hajji Kandil, or Tall al-'Amarnah, the Frenchman left the train,

and set out to try to buy some of the tablets said to have been

found at Tall al-'Amarnah, and as he left the station some of

the police from the train followed him. At Asyut, the Maltese

and myself embarked on the steamer, and the remainder of the police

followed us. As the steamer tied up for the night at Akhmim and

Kana I had plenty of time at each place to examine the antiquities

which the dealers had in their houses, and to bargain for those

I wanted. At Akhmim I found a very fine collection in the hands

of a Frenchman who owned a flour-mill in Cairo, and he caused

the police to be entertained at supper whilst he and I conducted

our deal for Coptic manuscripts. He told me that it was he who

had sold to Maspero all the Coptic papyri and manuscripts which

the Louvre had acquired during the last few years, and then went

on to say that if he had known that Maspero intended to dispose

of these things he would not have let him have them at such a

low price. Thus I learned at first hand that the Director of the

Service of Antiquities had bought and disposed of anffquities,

and exported them, which the British authorities in Cairo declared

to be contrary to the law of the land.

As there was work for me to do in Aswan, I decided to make no

stay in Luxor on my way up the river, but during the few hours

which the steamer stopped there I learned from some of the dealers,

and from my friend, the Rev. Chauncey Murch of the American Mission,

some details of the "finds" which had been made. I took

the opportunity of sending a couple of natives across the river

to fetch me skulls for Professor Macalister, who wanted

more and more specimens. During one of the visits which I

made to Western Thebes the previous year I was taken into a huge

cave at the back of the second row of hills towards the desert,

which had been used by the ancient Egyptians as a cemetery. There

I saw literally thousands of poorly-made mummies and "dried

bodies," some leaning against the sloping sides of the cave,

and others piled up in heaps of different sizes. I had no means

of carrying away skulls when I first saw the cave, or I should

certainly have made a selection then.

There was little to be had at Armant, but I saw at Jabalen, which

marks the site of Crocodilopolis, a number of pots of unusual

shape and make, and many fiints. On arriving at Aswan I was met

by Captain W. H. Drage (now Colonel Drage Pasha) and Doone Bey,

who gave me much assistance in packing up the remainder of the

Kufi grave-stones, which I had been obliged to leave there earlier

in the year. My friend, the Ma'amur, produced a further supply

of skulls from the pit in the hill across the river, and I learned

incidentally that the natives had nick-named me "Abu ar-Ra'wus,"

or "father of skulls." The general condition of the

town had changed astonishingly, for the British soldiers had departed

to the north, their camps and barracks were deserted and as silent

as the grave, and Aswan was just a rather large sleepy Nile village.

And the change across the river was great. The paths which we

had made with such difficulty were blocked with sand, and the

great stone stairway and the ledge above it were filled with sand

and stones which had slid down from the top of the hill, and the

tombs were practically inaccessible.

Soon after my return to Luxor I set out with some natives one

evening for the place on the western bank where the "finds"

of papyri had been made. Here I found a rich store of fine and

rare objects, and among them the largest roll of papyrus I had

ever seen. The roll was tied round with a thick band of papyrus

cord, and was in a perfect state of preservation, and the clay

seal which kept together the ends of the cord was unbroken. The

roll lay in a rectangular niche in the north wall of the sarcophagus

chamber, among a few hard stone amulets. It seemed like sacrilege

to break the seal and untie the cord, but when I had copied the

name on the seal, I did so, for otherwise it would have been impossible

to find out the contents of the papyrus. We unrolled a few feet

of the papyrus an inch or so at a time, for it was very brittle,

and I was amazed at the beauty and freshness of the colours of

the human figures and animals, which, in the dim light of the

candles and the heated air of the tomb, seemed to be alive. A

glimpse of the Judgment Scene showed that the roll was a large

and complete Codex of the Per-em-hru, or "Book of the Dead,"

and scores of lines repeated the name of the man for whom this

magnificent roll had been written and painted, viz., "Ani,

the real [as opposed to honorary] royal scribe, the registrary

of the offerings of all the Gods, overseer of the granaries of

the Lords of Abydos, and scribe of the offerings of the Lords

of Thebes." When the papyrus was unrolled in London the inscribed

portion of it was found to be 78 feet long, and at each end was

a section of blank papyrus about 2 feet long. In another place,

also lying in a niche in the wall, was another papyrus Codex of

the Book of the Dead, which, though lacking the beautiful vignettes

of the Papyrus of Ani, was obviously much older, and presumably

of greater importance philologically. The name of the scribe for

whom it was written was Nu, and the names of his kinsfolk suggested

that he flourished under one of the early kings of the XVIIIth

dynasty. In other places we found other papyri, among them the

Papyrus of the priestess Anhai, in its original painted wooden

case, which was in the form of the triune god of the resurrection,

Ptah-Seker-isar, and a leather roll containing Chapters of the

Book of the Dead, with beautifully painted vignettes, and various

other objects of the highest interest and importance. I took possession

of all these papyri, etc., and we returned to Luxor at daybreak.

Having had some idea of the things which I was going to get, I

had taken care to set a tinsmith to work at making cylindrical

tin boxes, and when we returned from our all-night expedition

I found them ready waiting for me. We then rolled each papyrus

in layers of cotton, and placed it in its box, and tied the box

up in gumdsh, or coarse linen cloth, and when all the papyri and

other objects were packed up we deposited the boxes in a safe

place. This done we all adjourned a little after sunrise to a

house (since demolised) belonging to Muhammad Muhassib, which

stood on the river front, and went up on the roof to enjoy the

marvellous freshness of the early morning in Egypt, and to drink

coffee.

Whilst we were seated there discussing the events of the past

night, a little son of the house, called Mursi, came up on the

roof, and, going up to his father, told him that some soldiers

and police had come to the house, and were then below in the courtyard.

We looked over the low wall of the roof, and we saw several of

the police in the courtyard, and some soldiers posted outside

as sentries. We went downstairs, and the oflficer in charge of

the police told us that the Chief of the Police of Luxor had received

orders during the night from M. Grebaut, the Director of the Service

of Antiquities, to take possession of every house containing antiquities

in Luxor, and to arrest their owners and myself, if found holding

communication with them. I asked to see the warrants for the arrests,

and he told me that M. Grebaut would produce them later on in

the day. I asked him where M. Grebaut was, and he told me at Nakadah,

a village about twelve miles to the north of Luxor, and went on

to say that M. Grebaut had sent a runner from that place with

instructions to the Chief of the Police at Luxor to do what they

were then doing-that is, to take possession of the houses of all

dealers and to arrest us. He then told Muhammad and myself that

we were arrested. At this moment the runner who had been sent

by Grebaut joined our assembly in the casual way that Orientals

have, and asked for bakhshish, thinking that he had done

a meritorious thing in coming to Luxor so quickly. We gave him

good bakhshish, and then began to question him. We learned

that M. Grebaut had failed to reach Luxor the day before because

the ra'is, or captain of his steamer, had managed to run the steamer

on to a sandbank a little to the north of Nakadah, where it remained

for two days. It then came out that the captain had made all arrangements

to celebrate the marriage of his daughter, and had invited many

friends to witness the ceremony and assist at the subsequent feast,

which was to take place at Nakadah on the very day on which M.

Grebaut was timed to arrive at Luxor. As the captain felt obliged

to be present at his daughter's marriage, and the crew wanted

to take part in the wedding festivities, naturally none of the

attempts which they made to re-float the steamer were successful.

Our informant, who knew quite well that the dealers in Luxor were

not pining for a visit from M. Grebaut, further told us that he

thought the steamer could not arrive that day or the day after.

According to him, M. Grebaut determined to leave his steamer,

and to ride to Luxor, and his crew agreed that it was the best

thing to do under the circumstances. But when he sent for

a donkey it was found that there was not a donkey in the

whole village, and it transpired that as soon as the villagers

heard of his decision to ride to Luxor, they drove their donkeys

out into the fields and neighbouring villages, so that they might

not be hired for M. Grebaut's use.

The runner's information was of great use to us, for we saw that

we were not likely to be troubled by M. Grebaut that

day, and as we had much to do we wanted the whole day clear of

interruptions. Meanwhile, we all needed breakfast, and Muhammad

Muhassib had a very satisfying meal prepared, and invited the

police and the soldiers to share it with us. This they gladly

agreed to do, and as we ate we arranged with them that we were

to be free to go about our business all day, and as I had no reason

for going away from Luxor that day, I told the police officer

that I would not leave the town until the steamer arrived from

Aswan, when I should embark in her and proceed to Cairo. When

we had finished our meal the police officer took possession of

the house, and posted watchmen on the roof and a sentry at each

corner of the building. He then went to the houses of the other

dealers, and sealed them, and set guards over them.

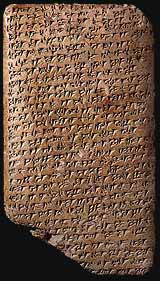

In the course of the day a man arrived from Hajji Kandil, bringing

with him some half-dozen of the clay tablets which had been found

accidentally by a woman at Tall al-'Amarnah, and he asked me to

look at them, and to tell him if they were kadim, i.e., "old"

or jadid, i.e., "new"-that is to say, whether

they were genuine or forgeries. The woman who found them thought

they were bits of "old clay," and useless, and sold

the whole "find" of over 300 tablets to a neighbour

for 10 piastres ( 2s. )! The purchaser took them into the village

of Hajji Kandil, and they changed hands for £10. But those

who bought them knew nothing about what they were buying, and

when they had bought them they sent a man to Cairo with a few

of them to show the dealers, both native and European. Some of

the European dealers thought they were "old," and some

thought they were "new," and they agreed together to

declare the tablets forgeries so that they might buy them at their

own price as "specimens of modern imitations." The dealers

in Upper Egypt believed them to be genuine, and refused to sell,

and, having heard that I had some knowledge of cuneiform, they

sent to me the man mentioned above, and asked me to say whether

they were forgeries or not; and they offered to pay me for my

information. When I examined the tablets I found that the matter

was not as simple as it looked. In shape and form, and colour

and material, the tablets were unlike any I had ever seen in London

or Paris, and the writing on all of them was of a most unusual

character and puzzled me for hours. By degrees I came to the conclusion

that the tablets were certainly not forgeries, and that they were

neither royal annals nor historical inscriptions in the ordinary

sense of the word, nor business or commercial documents. Whilst

I was examining the half-dozen tablets brought to me, a second

man from Hajji Kandil arrived with seventy-six more of the tablets,

some of them quite large. On the largest and best written of the

second lot of tablets I was able to make out the words "A-na

Ni-ib-mu-a-ri-ya," i.e., "To Nibmuariya,"

and on another the words "[A]-na Ni-im-mu- ri-ya shar matu

Mi-is-ri," i.e., "to Nimmuriya, king of the land

of Egypt." These two tablets were certainly letters addressed

to a king of Egypt called "Nib-muariya," or "Nimmuriya."

On another tablet I made out clearly the opening words "A-na

Ni- ip-khu-ur-ri-ri-ya shar matu [Misri] )," i.e., "To

Nibkhurririya, king of the land of [Egypt,"] and there was

no doubt that this tablet was a letter addressed to another king

of Egypt. The opening words of nearly all the tablets proved them

to be letters or despatches, and I felt certain that the tablets

were both genuine and of very great historical importance.

Up to the moment when I arrived at that conclusion neither of

the men from Hajji Kandil had offered the tablets to me for purchase,

and I suspected that they were simply waiting for my decision

as to their genuineness to take them away and ask a very high

price for them, a price beyond anything I had the power to give.

Therefore, before telling the dealers my opinion about the tablets,

I arranged with them to make no charge for my examination of them,

and to be allowed to take possession of the eighty-two tablets

forthwith. They asked me to fix the price which I was prepared

to pay for the tablets, and I did so, and though they had to wait

a whole year for their money they made no attempt to demand more

than the sum which they agreed with me to accept.

I then tried to make arrangements with the men from Hajji Kandi1

to get the remainder of the tablets from Tall al- 'Amarnah into

my possession, but they told me that they belonged to dealers

who were in treaty with an agent of the Berlin Museum in Cairo.

Among the tablets was a very large one, about 2o inches long and

broad in proportion. We now know that it contained a list of the

dowry of a Mesopotamian princess who was going to marry a king

of Egypt. The man who was taking this to Cairo hid it between

his inner garments, and covered himself with his great cloak.

As he stepped up into the railway coach this tablet slipped from

his clothes and fell on the bed of the railway, and broke in pieces.

Many natives in the train and on the platform witnessed the accident

and talked freely about it, and thus the news of the discovery

of the tablets reached the ears of the Director of Antiquities.

He at once telegraphed to the Mudir of Asyut, and ordered him

to arrest and put in prison everyone who was found to be in possession

of tablets, and, as we have seen, he himself set out for Upper

Egypt to seize all the tablets he could find. Meanwhile, a gentleman

in Cairo who had obtained four of the smaller tablets and paid

£100 for them, showed them to an English professor, who

promptly wrote an article upon them, and published it in an English

newspaper. He postdated the tablets by nearly 900 years, and entirely

misunderstood the nature of their contents. The only effect of

his article was to increase the importance of the tablets in the

eyes of the dealers, and, in consquence, to raise their prices,

and to make the acquisition of the rest of the "find"

more difficult for everyone.

---------

From 'By Nile and Tigris'

(1920) by Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge